One of the precepts for my journey is that both private and public education have much to offer in terms of innovation for the future. They face different challenges in terms of funding, politics, value proposition, and demographics, but learning is not public or private, it is learning. Already in the last two weeks we have seen how public schools are leading in some ways, and private schools with very modest means are leading in others. We can learn from each and leverage aspects of the paths they are on. If you are interested in entrepreneurial instruction, new ideas for science programs, character and leadership training, student wellness, and how it all gets done, read on!

We will all agree from the outset that The Culver Academies have a very large resource base and are not typical in that regard of many other schools in America. Culver is old and has unique traditions would around its core value of training leaders. Those who would discard lessons we can learn from them should think twice. There are great things going on at Culver, and we may need to tweak how we use these lessons, but they are still extremely valuable.

We will all agree from the outset that The Culver Academies have a very large resource base and are not typical in that regard of many other schools in America. Culver is old and has unique traditions would around its core value of training leaders. Those who would discard lessons we can learn from them should think twice. There are great things going on at Culver, and we may need to tweak how we use these lessons, but they are still extremely valuable.

Harry Frick leads the Ron Rubin School for the Entrepreneur at Culver, featuring a college-level four-course curriculum on innovation, start-ups, modeling new ventures, and entrepreneurial leadership. To their knowledge this is the only one of its type at the secondary level in the United States. Students are linked outside of the classroom via field trips to businesses, and many have taken on internships as well. The School is sponsoring a business plan competition and will expand to other challenge-based projects in the future. According to Harry, the goals of the program are similar to those espoused by Columbia Business School Dean Glen Hubbard: “Analyze, Decide, Lead”.

The Culver science department looks and operates like a small university lab model. Josh Pretzer, Chris Carrillo, and other of the science faculty have set up high school-appropriate research opportunities for students to engage in real world experimentation under the guidance of faculty who are engaging in areas of their own interests. As Chris said, “We want to give students the opportunities that we did not get until we were in college to get excited about scientific research”. They have active programs in synthetic fuels, biomass energy generation, microbial fuel cells, and native and non-native plant species. They are using technology to simulate classic experiments in physics that cannot be conducted in a high school setting, and applying the results to modern problems. The faculty at Culver have lighter teaching loads than at many other schools, allowing them to engage in this kind of research, but there were several keys that any school can leverage regardless of teaching loads or resources:

- Connecting with university researchers who almost always have to include some element of community outreach on their NSF grants.

- Hiring new faculty who actually have active outside research interests and can pursue them with students in creative ways.

- Using technology to link to massive experimental and research organizations like NASA and CERN.

The important takeaway from the science department is that they are creating ways for students to pursue their own passions along with those of faculty. This creates an energy that extends well beyond the classroom…just as we saw at a modest public school like MRHMS in St. Louis. (In fact, I think these two schools should really get together and cooperate on some research between fired up high school and middle school students!)

Chris and Josh also reviewed for me the process that Culver uses for self-evaluation of their departmental work. Every three years, each department does a self-study using a team of external colleagues to come in and review their teaching and program. This was not forced on the Culver faculty by an anxious administration, they asked for it. At first it was a leap of faith, with some fearing it would be overly intrusive. According to Chris, now there is huge support for it, and the departments eagerly look foreword to the cycle and the chance to reflect and improve their practices.

Chris and Josh also reviewed for me the process that Culver uses for self-evaluation of their departmental work. Every three years, each department does a self-study using a team of external colleagues to come in and review their teaching and program. This was not forced on the Culver faculty by an anxious administration, they asked for it. At first it was a leap of faith, with some fearing it would be overly intrusive. According to Chris, now there is huge support for it, and the departments eagerly look foreword to the cycle and the chance to reflect and improve their practices.

John Yeager has worn a lot of hats at Culver and is now the Director of the Center for Character Excellence. John studied at UPenn on issues related to resilience, character strengths, relationships, and growth mindsets. He is co-author of Smart Strengths, and has set up this program to enhance student wellness in all aspects of student life. By training both faculty and students in the use of strength inventories, they are developing a consistent language of how students can develop a positive core of organizational and emotional skills to become good architects of their own choices. John is teaching an elective course in metacognition with the goal of getting students comfortable with things like ambiguity, challenge, and risk management. John feels his work helps gives students a range of options of how to think about themselves and to understand some of the fundamental attribution errors that can lead to bad choices down the road. They are building in significant elements of reflection, including bringing yoga into the class to teach aspects of mindfulness. As part of the pilot, they will work on exporting the key lessons out to other departments, and are also interested in exporting this to other schools and other communities. (Hear that? They are interested in helping set this up at other schools!)

A final note from John: this work is highly metacognitive, which they see as a major component of leadership, the key to the Culver brand. They have successfully marketed the strength of this brand to colleges, who understand that a focus on leadership at Culver may sometimes trump a student taking the extra AP courses. It seems to work just fine for their graduates.

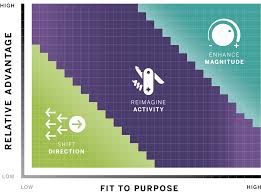

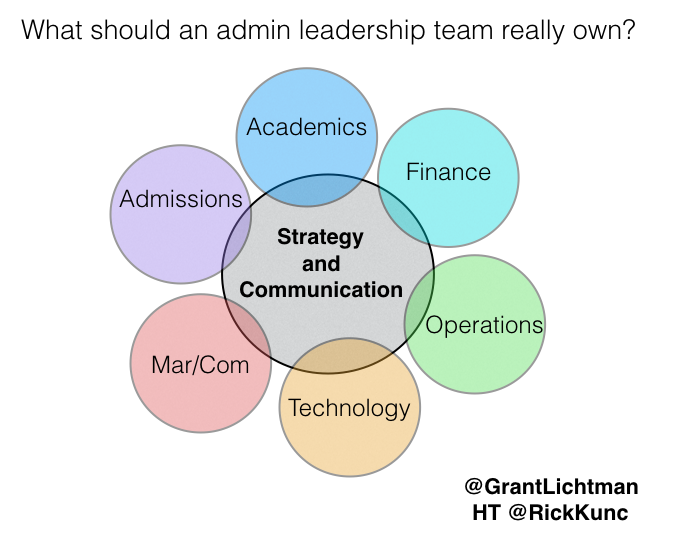

Kathy Lintner and Kevin MacNeil are two of the academic leader brain trust at Culver, and we talked about how the school views innovation and change. This is, after all, an institution of more than 120 years, steeped in both civil and military tradition, set in the middle of the Indiana countryside. It may not seem like a hotbed of progressive pedagogy; that is not its mission or brand. But that does not mean that change is absent, and in fact, as I saw, in many ways they are highly adaptive and innovative within a time frame that aligns with their traditions. The results are come courses like I have described that can only be described as tightly aligned with a progressive model. Kathy and Kevin outlined several keys to how they approach new ideas in order to maximize effective implementation:

- Take the time to be proactive. Reactive is a bad way to institute change. They build time into their structures to ensure they are thinking about issues before they become critical.

- Build and maintain a clear vision. Faculty are rarely consensual and it is tough to build consensus if there is not a vision to build around.

- Ensure strong leadership all the way from the board down through the head and the department chairs. Change is tough and it won’t work if it is one person doing the lifting.

- Focus on details and have the patience to add detail where needed.

- Create incentives and put accountability protocols in place.

Lacking any one of these, they say, and change falters. (I might add, they did not have to go to their notes to rattle off these keys; they are on the front burner, not sitting in some plan on the shelf.) Kathy noted another real key: their entire leadership team has been together for 14 years. I have noted elsewhere the difficulty of creating change at schools where the sine wave of head turnover, overlapped on the sine wave of board turnover leaves incredibly small (if any) windows for real change to take place.

Expanding on a couple of these points, Culver has a possible unique faculty assessment process that looks are four attributes of performance:

- Commitment to mission

- Teaching and learning model

- Professional growth

- Cultivation of character

They have annual discussions about these four standards that yield commendations and recommendations for the teachers, but have nothing to do with pay. Pay increases are based on rank and promotion, independent of years of service, but rather based 100% on performance and the accumulated record of the annual performance reviews.

With respect to the rate of change, Kathy emphasized that innovation can happen quickly but real change in a school takes time. It is up to the leadership team to recognize the right rate of change. I cannot end without saying that every member of this team I met with at Culver told me that this steady, intentional, thoughtful style of real change could not have been possible without the leadership of the President, John Buxton. I won’t go into every accolade, as I am sure Mr. Buxton would not want me to. John Yeager, however, probably summed up their thoughts best when he said that since Buxton has taken over at Culver “there is the same feel, but now we have a growth mindset of continuous improvement. John has shown us how tradition and innovation can effectively mix.”

As with other posts, I have gone on too long yet still offered only a fraction of what I learned at Culver. I would encourage schools, particularly those with truly limited resources, to reach out and talk to folks at Culver. Yes, they have a big endowment and boys wear uniforms. But this is an institution that is “thinking and doing” deeply in concert with their mission, and that mission includes being a very intentional part of the greater community.

Leave A Comment