Did a 9th grader just solve one of the most intransigent obstacles to school innovation? I think so! It is a simple, elegant, easy way to create large blocks of time for faculty to collaborate on their own professional development and growth. Read on and send comments; is there a hidden thorn in this rose I don’t see?

Did a 9th grader just solve one of the most intransigent obstacles to school innovation? I think so! It is a simple, elegant, easy way to create large blocks of time for faculty to collaborate on their own professional development and growth. Read on and send comments; is there a hidden thorn in this rose I don’t see?

Two weeks ago I asked a group of 9th graders to observe and journal on how learning takes place at All Saints’ Episcopal School in Ft. Worth. After a short campus walk the students itemized their observations and then pitched ideas to the group about how learning might be more closely tied to their own lives and objectives. I have reported on their remarkable insights, but one stood out and I have subsequently run the idea by a number of colleagues. Is this the no-brainer we have been overlooking?

Many of our classrooms at all grade levels are becoming project-based, and good projects are designed to include time for student collaboration, research, making, designing, building, and creating. What if we just aligned the days and times when many classes were doing this kind of largely independent work? What if, say, every other Thursday for a half-day, all or many classes at the school had “project time”? A very few faculty could supervise a large number of students during these collaborative work times, releasing the rest for large, frequent blocks of professional growth time.

Yesterday I pitched the idea to the team who will be opening the new K-8 Design 39 Campus in Poway, CA next year. Their heads exploded with understanding of the upside of this plan. Merely be getting teachers to align when they provide students time for major periods of collaboration, they will radically increase professional development time. Nothing is taken out of the curriculum; time is created by alignment.

Obstacles? If your school has many small blocks of teaching time the alignment will be slightly more complex than if you have longer teaching blocks. Younger students will probably need more adult supervision than older students. I can’t think of any others, but maybe you can; please pass them along.

Upside? Many faculty with large blocks of free time to frequently work across silos. The D39C team may set a goal of half the faculty freed up for a half-day every two weeks. One of the ideas I shared with Dave Ostroff at All Saints’: get several nearby schools on the same schedule and create interscholastic PD blocks.

I have gathered more than 1,200 “What if…?” questions from educators, students, and parents over the last 9 months. This is in the top five. Time for PD is the most commonly cited obstacle to school innovation. Ask your teachers: would you be willing to flex your alignment of student-led project time if it meant a half-day every two weeks of authentic professional growth? I am confident of the response!

Grant,

I do think that this student is on to something quite simple, really. There are complexities abound in its implementation, which would be interesting to sit down with a faculty to talk more about. The one thing that I would second is your statement about the differences in time and supervision required at different age levels.

Perhaps an added component can be this– I think it would be extremely beneficial to have times throughout a project or design where we would want to have a heavy dose of adult time with students– even more than their regular teacher. So why not plan for “heavy dose” days where the entire faculty was available to work with students on their projects, giving alternative thoughts and feedback than they may get from their classroom teacher and then plan for subsequent “light” days where students need less adult time/attention and more self time and attention to work independently. By aligning this with teachers’ own “heavy dose” days (regular PD days) and lighter days where they can capture time and partnership, boy we could accomplish some great things!

Great idea: heavy and light dose days!

I continue to be challenged by the traditional mindset of “professional development” no matter when it occurs, or what the newest breakthrough might be.. Why do educators have to wait for learning? Why must it be scheduled? Why does it have to occur once every two weeks? The bigger question at hand is not professional development, which is something done to teachers – but a question that focuses on teachers as learners. Do they learn independently on their own, follow their own passions, and grow in directions that serve student learning, without having to wait for motivation and opportunity from another source? And, how do you know? If you asked teachers to document what they learned on their own, and how they did it, would be a truly compelling set of questions. Too much of education looks towards innovating traditional and dated structures rather than looking forward. Too many schools seek to become better at a 1997 version of school.

David,

I think in a perfect world you are absolutely correct. But consider the public district where teachers have 200+ students and time for peer-to-peer collaboration has been chopped due to budget cuts. It is really hard to tell those folks to carve more time out to learn on their own. On my many school visits, this is THE most commonly cited issue: most (not all) teachers work long hours and are not paid all that well. If we can create that time WITHOUT adding to total hours committed, why not?

Thanks!

There are many recipes for the same dish. As far as this one goes, I would encourage those schools for whom this works – or might work – to try it. Especially All Saints, because that’s where the ethnography produced the idea, and because it would value those students’ observations and insights to take it to a prototyping phase and experiment.

When I was a middle school principal, we experimented with 8 different ways to provide collective/collaborative time for faculty to think-and-do with each other. Through this experimentation and discovery, we eventually landed on a powerful model that we adapted for our own intensive work – PLCs. Of course, we kept some of the other structures we discovered, too.

A couple of other thoughts come to mind:

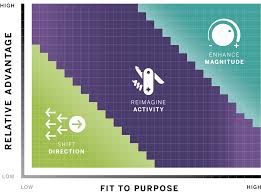

1) I totally and completely agree with David Jakes! At the same time, I think schools must at least consider – and even better, implement – a practice of managing a complex innovation portfolio. In this case, the “school” should be trying several approaches to address and solve the problem. There should be some rapid, low-res prototyping to work the problem in certain ways before having to change a thing. From these insights, more production-oriented trials could be attempted. Among the options, an innovation portfolio would manage various tiers of means. Some more radical and some less radical. In these spaces, one would find some of the intersections in what David and you say.

2) For me personally, I would want to think that the faculty and students are working together on the projects as co-learners and co-citizens. Even collaborating with the community beyond the walls of the school house. So, it makes less sense for me that students would be in one area and faculty in another. For me and my current school, it makes more sense for us to be co-learning and co-working — TOGETHER!

What I think is powerful about this idea is the focused examination of what might be possible in a particular setting and how one then moves from the possible to the transformative.

In our middle school, we realized several years ago that there were times during the week when almost all teachers at a grade level were free (e.g., all of the students were at PE). This time had always existed, but was being used by individuals to serve individual needs. For a long time, we had been talking about our need for space/time for collaboration, but we simply weren’t seeing what was in front of us.

When we shifted our perspective slightly and saw this time in the context of what it might afford for collective work between colleagues, we suddenly found a home for our professional learning groups without having to tack another meeting on to the day.

We’ve also found that by building this formal collaboration time into the schedule and honoring a time for professional dialog, the nature of and perhaps more importantly the role of the kind of dialog in informal spaces/times has also increased and led to new opportunities for innovation.

I also think that Bo is exactly right in pushing us to figure out how to create space/time where students, teachers and others beyond the school are learning together. This is a kind of “undiscovered country” that will truly transform what schools can and should be.

Thanks, Mark and Bo, for adding to this discussion! The only thing I would add back in response is that I would not see the time as separating teachers and students in an arc of learning; there are times when we want adults to be at hand and other times when we should let students be with themselves; these are not mutually exclusive.

This of course highlights the point that a lot of our PD can actually come FROM the students, as this very idea did. I used to think anything I wanted to teach my students I had to master myself prior to introducing. It took me way too many years to understand that I could learn from my students. This sounds like a simple point. Sit and watch how students engage in PBL and you will learn tons. However, I have observed the “fear” of teachers as they enter a STEM based, exploratory center with students, and the flow of student questions they can not answer begin. You have to be comfortable outside of your comfort zone, and want to conquer your fears, and then the learning (either with students or without) can begin. And I am not going to suggest that is easy.

Thanks, Margo, and I completely agree. But remember to get people to separate what is hard from what is uncomfortable!