On the plane rides to and from my workshop presentations at NAIS and NBOA in Florida I had a chance to read in detail the latest issue of Independent School Magazine. Yes, my own article on mutation and zero-based strategic thinking is in the issue, but I want to share some call-outs from several of the other articles since many of my readers just do not have access to, or time to read, this excellent issue. I find these articles valuable for all forms of schools; public and private schools and their leaders share vastly more ground than that which separates us.

Stephen Valentine, administrator and teacher at Montclair Kimberley Academy, New Jersey added to the conversation of strategic leadership with his article “In the Maelstrom of American Independent Education”. Following are some quotes from the article and my comments:

John Seeley Brown: “every 18 months to two years he has to ‘completely reinvent the skills and practices’ he uses.

Is this realistic for a school leader? The world does not give us an option; only the opportunity to choose what reinvention means for each of us. Our students are constantly reinventing their “skills and practices”, some because we ask it of them (that is what we call “learning”) and some completely on their own with neither direction nor assistance from any adult. Should we not model life-long learning for our students if that is what we want of them? And is this an unreasonable time frame given the changes in the world around us? I know educational site leaders who believe that this is now part of the job description of all teachers and administrators.

Adopting a school culture of openness and experimentation—of continuous learning—is the best way to leverage our missions in our time.

This is easy to say…but not so easy to implement across a school organization. Most of our schools are not culturally comfortable with experimentation that leads to a constant roil of change. The most important element in developing this culture is leadership that expects and rewards experimentation; that supports risk-taking; and publicly rewards those who lead through innovation practices.

Following lead by Mark Crotty, Head of School at St. John’s Episcopal: Leaders of initiative-rich schools should establish “’parameters of continuation’’…leaders need to know when to take an initiative off the table or move resources elsewhere.

We make plenty of wagers but far fewer pivots than we should.

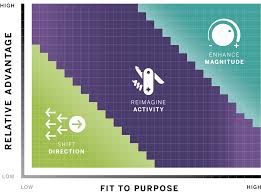

We must remind ourselves that successful innovation is NOT the adoption of new ideas, or even the adoption of GOOD new ideas. It is the implementation of new ideas that enhance the value of the organization. We probably have to reject more ideas than we pursue. Leaders, as Mark Crotty tells us, must set out parameters for success, and be just as open and bold in pivoting away from pilots as they are in supporting their growth. They must develop the trust amongst their teams that failure to pursue a pilot is not a rejection of personal value, but rather appropriate alignment of the relatively scarce resources at our control.

Your team, or at least someone on your team, needs to be connected to other thinkers and doers—and not just via the occasional conference.

On this point I think Valentine can go much further. Yes, schools need a point person or team to promote active connectivity between the school and the vast developing neural network of knowledge creation and sharing that I have dubbed the cognitosphere. We see the rise in a new position at schools, or a re-tooling of the old “Dean of Faculty”: the Chief Innovation Officer. But we should not relegate this task to one person or one team. Now, and increasingly in the future, connectivity will be a critical pathway of personal growth and learning. Simply, to be effective learners (which is everyone in a school) we ALL must be connected to other thinkers and doers, wherever they are.

The modern seeker finds and shares, contributing to and deriving benefits from, the flow of knowledge.

In the recent past we derived tangible benefits from protecting our sources and products of knowledge. Students worked alone and were rewarded for getting a better result than others in the class. Scientists published first or not at all. Professionals held onto their entire work product in order to gain advantage in the market place. While there will always be closely-held proprietary work, the amount of open sharing now engaged across all knowledge based industries is staggering, and those who contribute and share the most derive real benefits for themselves and for their organizations.

Next up: John Gulla and Olaf Jorgenson’s article on measuring success.

I agree on two major points here – (1) less separates public and private education/educators than we think and (2) I have been so informed and impressed by NAIS’ publication The Independent School over the years that I subscribed as a parent for a decade. Highly recommend the investment to anyone concerned about American pedagogy.