My second full day at Presbyterian Day School in Memphis was just as eventful as the first; this mid-sized elementary school continued to surprised me with an array of truly leading edge programs in character education, global awareness, health and fitness, tailored learning in reading, curriculum development, an exceptional virtual social studies program, and more. Jamie Baker, strategic leader of the affiliated Martin Institute for Teaching Excellence repeated what I heard over and over from faculty and staff: head Lee Burns “is a perforator who brings outside ideas to the school, and manages a portfolio of innovation projects in the pipeline at all times.” As Jamie says, “excellence is never accidental. Innovation requires leadership, vision, and courage. Lee is a cut above; he invites people to be responsive to his vision.”

Lee and Chaplain Braxton Brady have published a book and video that supports their “Building Boys, Making Men” program of character development, a class that meets once each rotation to focus on what they have defined as seven key virtues of positive character in men (PDS is an all-boys school). The boys help develop and present the material and do extensive reflective writing. While PDS is a Christian school, and the course does promote faith-based values, the vast majority is secular, including a unique list of key life skills that they guarantee boys will know by the time they graduate 6th grade. As a parent, I have to reprise this entire wonderful list here:

Lee and Chaplain Braxton Brady have published a book and video that supports their “Building Boys, Making Men” program of character development, a class that meets once each rotation to focus on what they have defined as seven key virtues of positive character in men (PDS is an all-boys school). The boys help develop and present the material and do extensive reflective writing. While PDS is a Christian school, and the course does promote faith-based values, the vast majority is secular, including a unique list of key life skills that they guarantee boys will know by the time they graduate 6th grade. As a parent, I have to reprise this entire wonderful list here:

- Doing a load of laundry (wash, dry, fold)

- Washing the dishes

- Ironing a shirt and pants

- Pump gas

- Cleaning a room (make bed, clean room, mop, dust, clean bathroom)

- Cook a basic meal

- Grill a hamburger

- Community service project

- Rules of dress (matching, dressing for occasions)

- Mowing, weeding, edging a lawn

- Tie a tie

- Start a fire

- Study for a test

- Drive a nail

- Write a handwritten thank-you note

- Conversation etiquette in person and on the phone

- Dating etiquette

- Basic first aid

- Give a speech

Braxton feels we have “become a reactionary parenting society. Parents don’t ask ‘what do I need to do now so my child will be ready to be an adult when they are 18’”. He feels that about 75% of the program is immediately transferable to a secular program, and they are planning to edit the book for just such an audience. I hope they do; many schools talk about infusing character education in their program, but don’t have a true program embedded in the curriculum. This is a great example to build on.

The Crain Center for Global Curriculum was initially funded to offer overseas professional development to PDS faculty, but it has grown into a signature program that is unusually rich for an elementary school. They have a partnership with a school in Buenos Aires, which already offers teacher exchanges and will now include student exchanges. The relationship has expanded through the school; students routinely Skype, blog, and share reading assignments with fellow students at the sister school. During the recent election, classes followed the election coverage through the Argentine press. Director of the Center, Darilyn Christenbury, says the goal of the Center is that “as students progress to adulthood, they will have a broader perspective of the world, and will be comfortable with managing multiple perspectives.” Most teachers at PDS have now included globally-focused elements into their subject curriculum, and students are encouraged to take action as part of authentic understanding and awareness.

The PDS Lifetime Fitness Center is not only unique for an elementary school; it may be unique for any school or any fitness center! The new facility includes a massive climbing wall with self-arresting repelling gear, vertical climbing challenges made of rope and wood, team-building type challenges that you might find at an Outward Bound camp, dynamic stationary bikes that can mimic BMX race courses or the Tour de France, and a range of light weights, jump ropes, balls, and hula hoops. The coaches teach the boys about health, diet, fitness, and how to gain strength (even though they don’t lift any heavy weights). The students learn to routinely self-monitor blood pressure, pulse and weight. And the faculty holds a daily spin class on the bikes! Students are in the Center several times a week, so the instruction is much more continuous than many one-off health and fitness programs.

The PDS Lifetime Fitness Center is not only unique for an elementary school; it may be unique for any school or any fitness center! The new facility includes a massive climbing wall with self-arresting repelling gear, vertical climbing challenges made of rope and wood, team-building type challenges that you might find at an Outward Bound camp, dynamic stationary bikes that can mimic BMX race courses or the Tour de France, and a range of light weights, jump ropes, balls, and hula hoops. The coaches teach the boys about health, diet, fitness, and how to gain strength (even though they don’t lift any heavy weights). The students learn to routinely self-monitor blood pressure, pulse and weight. And the faculty holds a daily spin class on the bikes! Students are in the Center several times a week, so the instruction is much more continuous than many one-off health and fitness programs.

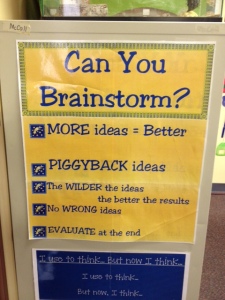

I sat in on a reading group that was re-enforcing their understanding of two stories they had read through a variety of brainstorming and systems thinking exercises. They used a trashcan to metaphorically analyze key elements of the two books through a model of “brainstorm wild ideas, piggyback, and withhold judgment.” Once they had developed some sound ideas to pursue, they engaged in a small group, rapid fire process of filtering, translating the main issues to the real world, collaborating on a solution, and a play-acting presentation, all in about ten minutes.

I looked around the room and realized that PDS has more post-it notes on the walls of classrooms and halls than a 3M laboratory. The students are almost always engaged in some form of design thinking-related information processing and analysis, so this kind of multilateral thinking has become truly second nature.

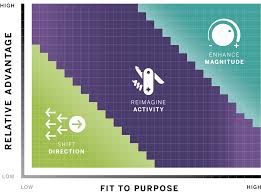

As I have commented several times on this trip, schools that successfully innovate have structures that are named and charged with the role; PDS is no exception. I had lunch with the Teaching and Learning Committee, a group of faculty with rotating membership that acts as incubator, gatekeeper, and facilitator of innovative practices. I heard time and again how faculty are encouraged to develop and try new ideas, experiment, pilot, fail, and tweak. The TLC helps review and validate ideas that come from the faculty, or develop strategies to implement broader vision projected from Lee and the other senior academic leaders. They say an average time to go from idea to essentially full implementation of a new pedagogy or major curriculum idea is 18-24 months, and sometimes they move much more quickly than that. The TLC is a resource to the entire faculty as they gather feedback and help with classroom implementation. Some quotes from the members:

- “A lot of what we implement, we know we are going to change in a year or so.”

- “Change and innovation is not the same for everyone. We encourage faculty to take an idea and then reform it to their particular needs. Change is done ‘by’ us, not ‘to’ us.”

- “We are told to question everything we do. We take all kinds of things off our list of what we teach as we add to them.”

- “We are comfortable with change, but let’s use ‘comfort’ broadly. We embrace change even though we do get tired; change is messy.”

- “A lot of what we do is transferable to other private and public schools, but the one limitation is mindset. If a school is ‘test-obsessed’, they are not going to have a growth mindset.”

I visited several other classrooms and saw more of the same fluid, student-centered, student-owned patterns of learning. In a reading class the students studied a set of black and white images from the era of civil rights conflict in the south and went through a group analysis to organize, filter, and associate the images into groups with similar content. In a 5th grade English/Communication class, groups of students were working together with the teacher on the side, researching a sustainability project they had developed to look at various options to limit waste in the cafeteria. They had started with basic research, localized it to the school, developed an action plan, created a Diigo site to share ideas and content, developed sets of guiding questions and answers, and iterated back to the start to validate their work. In a science class, the students were deep into a multi-week study of the nature of flight. The teacher uses open-ended questions to broadly direct the learning, but the students are asking, probing, questioning, sharing ideas, refining hypotheses together, and testing. Teacher Kim Bullard: “I start with big questions and let the students figure out how to create answers. I don’t give them any answers. We start at the high levels of abstraction and the students fill in the content they need to understand the problems they uncover.”

I visited several other classrooms and saw more of the same fluid, student-centered, student-owned patterns of learning. In a reading class the students studied a set of black and white images from the era of civil rights conflict in the south and went through a group analysis to organize, filter, and associate the images into groups with similar content. In a 5th grade English/Communication class, groups of students were working together with the teacher on the side, researching a sustainability project they had developed to look at various options to limit waste in the cafeteria. They had started with basic research, localized it to the school, developed an action plan, created a Diigo site to share ideas and content, developed sets of guiding questions and answers, and iterated back to the start to validate their work. In a science class, the students were deep into a multi-week study of the nature of flight. The teacher uses open-ended questions to broadly direct the learning, but the students are asking, probing, questioning, sharing ideas, refining hypotheses together, and testing. Teacher Kim Bullard: “I start with big questions and let the students figure out how to create answers. I don’t give them any answers. We start at the high levels of abstraction and the students fill in the content they need to understand the problems they uncover.”

Finally, I met with a group of 6th graders, and separately with their teachers, Jean Nabers and Melissa Smith, who have developed an advanced online history course. The course, History Through the Lens of Controversy, is now in its second year. There are about a dozen PDS students as well as students taking the class remotely in both Argentina and Texas. The course is housed on a Haiku site where the teacher posts readings, videos, and other source links, along with assignments. According to the boys, they are allowed and encouraged to go deeply into the subjects that interest them; according to the teachers they sometimes have to limit the amount of writing that the students can turn in. The boys were convincing in their passionate defense that this self-paced, deeper look at history is much better than the more traditional, fact-oriented regular class. “The work comes out of our minds. We get to go deeper. We write a lot of reflections. We will retain more of the knowledge.” Both teachers and students say that the online sharing of ideas is rich, and frequent, and that students often will change their own viewpoints after reading what a classmate has posted on a chat, voice thread, or a blog.

Jean says she wrote the course to offer “opportunities to stretch the students, to go deeply into topics that interest them”. As with the science class I visited earlier, the course material starts with abstract levels of interest and then creates opportunities for the students to fill in supporting content. Students can come see the teacher in person if they want, but what Jean has found is that the students help each other and work together without direction from her to do so. They are increasingly independent in their thinking and learning. The final assessment is a combination of student-selected work from the term and a written essay on the question “is war ever justified?”

It was an exhausting day filled with such an array of non-traditional learning. My main takeaways:

- PDS faculty innovates because they can, and because they know that what was good education in the past is no longer a standard.

- PDS has either reached, or is very close to reaching, a steady state where they are comfortable with ongoing change (which will likely be my suggested definition of organizational self-evolution).

- Faculty are supported in taking risks and with every bit of PD the administration can find.

- There is little or no ego of ownership amongst the faculty and staff; it does not matter who comes up with the idea or carries it forward. If it leads to better learning, all feel share in the success.

- Many teachers at PDS have completely changed how and what they teach over the period of 4-5 years. All teachers at PDS have changed a good portion of what and how they teach in that same time frame.

- Traditional sit-and-get learning is virtually gone. Students own their learning and teachers are there to coach, lead, and mentor. Teachers are using every means of systems and design thinking to get students to find the deep meaning within subject areas.

- When PDS decides to tackle a new direction, they go all-in more quickly than most schools. They do not pay lip service to things like health, fitness, character, or global awareness; they develop robust programs in-house, tweaking them frequently.

I have one more day at PDS later this week, but will have three other school visits to report on before that. Oh yes, and Jamie Baker parked her Smart car into a spot on Front Street that I would have thought half-big enough, with room to spare!

[…] morning I saw a great post by Grant Lichtman about Presbyterian Day School, a k-6 boys school in Memphis, TN, and coincidentally, the school I attended for kindergarten and […]

[…] Leading Classroom Change Permeates Presbyterian Day School, November 27, 2012 […]