America is not rural Nebraska. America is not suburban California. America is not 1955 and it is most certainly not 1776, 1863, or 1908. America is ALL of America, equal parts past, present, and future. Sen. Ben Sasse knows this…at least some of it. In Part One of this three-part blog series on Sasse’s book The Vanishing American Adult, I applauded much of both Sasse’s thinking and findings with respect to the challenges, role, and future of American education. I ended the book and the blog with real optimism that Sasse, a conservative representing a deep-red state, and I, a progressive from a deep-blue state, might find such overlapping ground on which to move forward for positive change in our schools.

Yet there are, in my humble opinion, critical flaws in Sasse’s narrative: a narrow myopia of life in America, both today and in the past, founded in Sasse’s personal and family stories and, most importantly to us today, in a mistaken, and often hypocritical conservatism that is driving policies harmful to education at national, state, and local levels. We need to explore these flaws with the same introspection as we celebrate his vision for better schools. I hope and believe that, if Sen. Sasse were ever to read this review, he would welcome informed opinions that contradict his own.

Yet there are, in my humble opinion, critical flaws in Sasse’s narrative: a narrow myopia of life in America, both today and in the past, founded in Sasse’s personal and family stories and, most importantly to us today, in a mistaken, and often hypocritical conservatism that is driving policies harmful to education at national, state, and local levels. We need to explore these flaws with the same introspection as we celebrate his vision for better schools. I hope and believe that, if Sen. Sasse were ever to read this review, he would welcome informed opinions that contradict his own.

A “Rich Nation”

Sasse paints a picture of America as a nation with “more material surplus than any other people” in the world, and very likely in the history of the world, where poverty rates have dropped dramatically relative to just a century ago. This wealth, he believes has created an America where:

- “We seem collectively blind to the irony that the generation coming of age has begun life with far too few problems.”

- “Our kids no longer know how to produce. They don’t grow up around work.”

- “Our offspring know neither the experience of work nor even their ignorance of the hidden work that keeps their grocery aisles overflowing and geopolitical tormentors at bay.”

- “Although well-meaning, our indulgent practices have tended to encourage complacency among our pampered offspring.”

It is, says Sasse, “a rich-nation problem. The riddle before us is how to construct alternative ways of building long-term character in an era when the daily pursuit of food and shelter no longer compels.”

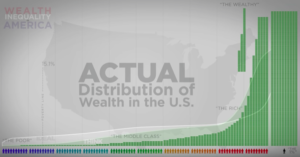

Sasse’s view is spot on for part of the American family, but highly skewed by his personal story and place. Intellectually he knows that this picture is not inclusive, yet it overwhelms his view of our nation and of the young people who comprise the rising generation. It overlooks the millions of Americans who go to bed hungry or undernourished every night; the children who work in the fields alongside their parents before and after school; the students at schools I visit who struggle to overcome violence in the streets, lack of decent clothing, fresh food, and Third World housing just to take care of their brothers and sisters and get to the refuge of school each day. This is not the America Sasse or I grew up in or live in today, but it is every bit as much of America as the one he writes about. And it is an America of extraordinary inequality, vastly greater than when he and I were young, where 1% of the people own 40% of the wealth and that, despite the conservative promise of trickle-down economics, is being driven further from, not closer to, the American dream.

Sasse’s view is spot on for part of the American family, but highly skewed by his personal story and place. Intellectually he knows that this picture is not inclusive, yet it overwhelms his view of our nation and of the young people who comprise the rising generation. It overlooks the millions of Americans who go to bed hungry or undernourished every night; the children who work in the fields alongside their parents before and after school; the students at schools I visit who struggle to overcome violence in the streets, lack of decent clothing, fresh food, and Third World housing just to take care of their brothers and sisters and get to the refuge of school each day. This is not the America Sasse or I grew up in or live in today, but it is every bit as much of America as the one he writes about. And it is an America of extraordinary inequality, vastly greater than when he and I were young, where 1% of the people own 40% of the wealth and that, despite the conservative promise of trickle-down economics, is being driven further from, not closer to, the American dream.

Sasse writes eloquently about the benefits of travel around the world to open our eyes; he needs to travel more to the schools and communities where the other America lives. In this blog space a few years ago we had a powerful tug-of-war about the notion of “grit”, with people like Paul Tough and Ira Socol pleading that many children in poverty in America exhibit all the “grit” in the world just to get to school each day; what they need is more “slack” in their lives, the kind that Sasse and I had as children, the support mechanisms that allowed us to grow into who we have become. Ben Sasse and I are not successful solely because we worked hard. We were also born in the right zip codes, which is, unfortunately, the best indicator of upward mobility for this rising American generation.

America IS a place of great wealth, and that wealth has become overwhelmingly concentrated in a very few hands. This is not political rhetoric; it is a fact. Unlike some conservatives, Sasse knows it. He argues that “we cannot assume that the middle class will easily self-perpetuate in the future”; that “the world of once-for-a-lifetime jobs is not coming back”; and perhaps if he were to move beyond rigid party politics he would agree that this future extends to coal miners in Appalachia and steel workers in Pennsylvania who will never move their families into the comfort of the American dream unless we move past the industries of the 19th and 20th centuries. Yet he fails to acknowledge that the middle class is already gone, that the middle class was not the result of trickle-down economics in either the 19th or 20th centuries, and that the increasingly extremist policies of both right and left, over the last 30 years, have killed the middle class American dream for a huge swath of Americans.

Sasse understands, at least in theory, the relationship between a thriving, vibrant, “leading” economy and education in America: “Yet just as the economy is laying the demand for a society of truly lifelong learners at our collective national feet, we have decided to orphan the rising generation of the American idea of universal dignity and the possibilities of resilience, innovation, and renewal.” He calls this “nothing short of a national existential crisis.” Those are big, challenging words. But a person of his experience and intellectual reach simply must draw the connection between failed policies that have created an America of extreme wealth and unacceptable poverty on the one hand, and the failures of education, parenting, and community awareness on the other.

Dewey

In #EdJourney I distilled what I saw in the many schools I visited down to a single word: Dewey. I said that, boiled down, Dewey’s philosophy of good education comes down to a simple formula: experience leads to passion, which leads to engagement, which leads to good, deep learning. I expect that Sasse largely agrees with that formula. He wants our kids to learn by doing, which is at the core of Dewey and the resurrection we are seeing today of a deeper learning model of post-industrial, student-centered education.

In #EdJourney I distilled what I saw in the many schools I visited down to a single word: Dewey. I said that, boiled down, Dewey’s philosophy of good education comes down to a simple formula: experience leads to passion, which leads to engagement, which leads to good, deep learning. I expect that Sasse largely agrees with that formula. He wants our kids to learn by doing, which is at the core of Dewey and the resurrection we are seeing today of a deeper learning model of post-industrial, student-centered education.

But rather than celebrating Dewey as one of the early progressivists who modeled the kind of education we now want to resurrect, Sasse chooses to excoriate Dewey as the chief Machievellian architect of an oppressive school system with profound socialist, or even communist overtones. Dewey, Sasse writes, “is responsible for allowing schools to undermine how Americans once turned children into adults. In Dewey’s dream, the school ceased to be an instrument supporting parents and became instead a substitute for parents.”

Sasse argues that Dewey’s teachings were largely responsible for creating a system that robs the family of the role of raising their own children. Dewey was, of course, a leader of the Progressive Era in more than just education, an awakening that brought to light the horrors of extreme poverty, servitude, racism, and child slave labor here and in other western democracies. To castigate him for intentionally creating a system in which the main purpose of school was to rob parents of their job as parents seems extremist. And, it does nothing to advance the current discussion, around which we can agree, that the learning lessons of Dewey are highly correlative to what Sasse and we want for our schools today.

Where Sasse, I, and even Betsy DeVoss agree, is that more choices for families in how their students can benefit from the time they spend in school is almost always a good thing. Many schools that are offering this increasingly differentiated buffet of quality education choices find their value proposition along some arc of the deeper learning model, which is rooted directly in the Dewey tradition of experiential learning, which Sasse appears to value for our children. Let’s start there. Let’s get the Department of Education laser-focused on supporting deeper learning for ALL students, not just those with the option to take their kids out of the neighborhood school and enroll them in a competing charter or private school.

Americanism

Finally, I find real fault in Sasse’s narrow reading of American history and the values that have made Americans unique. Like many of us, Sasse wants America to reflect the values that drove our founding fathers to courageously embark on this great social and political experiment. He calls on us to see an America through the lenses of Jefferson, Hamilton, Madison, Rousseau, deToqueville, Lincoln, and Teddy Roosevelt. Yet in this calling, his glasses are far-too rose-tinted. He, like many conservatives, wants the America of today to be a modern version of the America of 200 years ago. He wants to forget that some of Roosevelt’s speeches were be so filled with paternalistic racism that they can be confused with those of Hitler. He wants us to imagine that 13 small, isolated, rural colonies, many of them only functional due to the finances of slavery, can be a static template for America today. He, like other far-right conservatives, believe that any power that was not explicitly given to the federal government in the Constitution must never be do delegated. But America today is vastly more complex than America of 1785, and we believe in equity for our citizens much more than we did then. Most Americans believe that we should protect the rights of all Americans, yet state and local governments continue to allow de facto segregation in schools, try to include prayer and exclude rational science, re-write the social history of America in our textbooks, and give much more money to rich schools than to poor schools. As a senator, Sasse must come to grips with the dissonance of his desire to provide great education for all children, and the conservative manifesto that ignores how manifestly some states and districts could not care less.

Finally, I find real fault in Sasse’s narrow reading of American history and the values that have made Americans unique. Like many of us, Sasse wants America to reflect the values that drove our founding fathers to courageously embark on this great social and political experiment. He calls on us to see an America through the lenses of Jefferson, Hamilton, Madison, Rousseau, deToqueville, Lincoln, and Teddy Roosevelt. Yet in this calling, his glasses are far-too rose-tinted. He, like many conservatives, wants the America of today to be a modern version of the America of 200 years ago. He wants to forget that some of Roosevelt’s speeches were be so filled with paternalistic racism that they can be confused with those of Hitler. He wants us to imagine that 13 small, isolated, rural colonies, many of them only functional due to the finances of slavery, can be a static template for America today. He, like other far-right conservatives, believe that any power that was not explicitly given to the federal government in the Constitution must never be do delegated. But America today is vastly more complex than America of 1785, and we believe in equity for our citizens much more than we did then. Most Americans believe that we should protect the rights of all Americans, yet state and local governments continue to allow de facto segregation in schools, try to include prayer and exclude rational science, re-write the social history of America in our textbooks, and give much more money to rich schools than to poor schools. As a senator, Sasse must come to grips with the dissonance of his desire to provide great education for all children, and the conservative manifesto that ignores how manifestly some states and districts could not care less.

* * * * *

I could go into vastly more detail about points of American history and the evolution of our social experiment on which Sasse and I disagree, but let me finish back on areas of common ground. Sasse says, and I mostly agree, that:

America is first and foremost an idea. It is not an idea only for Americans. But it is an idea that Americans would proclaim on the world stage. Our forefathers and mothers spoke of self-evident truths and unalienable rights; they spoke not about blood and soil and tribe. To be an American meant sharing in this proposition laid out in the Declaration about where rights come from. You could be born an Englishman or a German or a Frenchman. But Americans are not just born; we are made.

At a national level, you and I each get one vote in about 100 million to create a better future for all of our children; Ben Sasse gets one vote in 100. He has one million times more opportunity to create conditions that will allow more Americans to actually live the American idea. But Sasse needs to understand and argue that America is a system as well as an idea. You can’t pick the few bits you like and throw out the rest. Ben Sasse knows this, but neither his voting record nor the policies of his party reflect it. That needs to change. There needs to be a “center” around which intelligent policy makers can find some elements of common ground. And that will be the subject of Part Three of this series.

Leave A Comment