Yesterday’s NPR report on the research by O’Boyle and Aguinis regarding the potential death of the bell curve standard has already started to provoke important conversation. Yesterday I took a first stab at how this research might impact how we view student performance and the structure of classes and assessment. Those are huge topics that will take a lot of thought and time to reconcile, but hopefully we will get started.

If you missed the reports yesterday, the links and summary of the research are here. Bottom line: new research shows that the bell curve in not, in fact, a good representation of a lot of human performance. Superstars account for much more of higher-end performances in many areas, which means that the non-superstars are performing at below our previous conception of average.

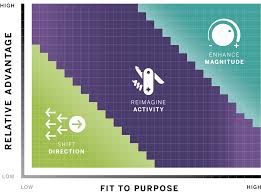

There is an equally compelling discussion, perhaps with even more foundational repercussions, in what these findings tell us about how our institutions, and in particular our schools, function. Specifically, how does this knowledge impact our decisions about innovation, and our ability to innovate in order to meet the challenges of a rapidly changing world?

If the research is correct, a few superstars are responsible for much of the top levels of performance. In schools, employee performance assessment is one of the touchiest sacred cows we have. Faculty are generally assessed by a combination of factors that focus on their management of classrooms and students. This is as it should be, at least in a stable environment. But what about when external stresses require us to adapt, evolve, and innovate? Who is going to lead that effort? Where are the superstars who will perform at the highest levels?

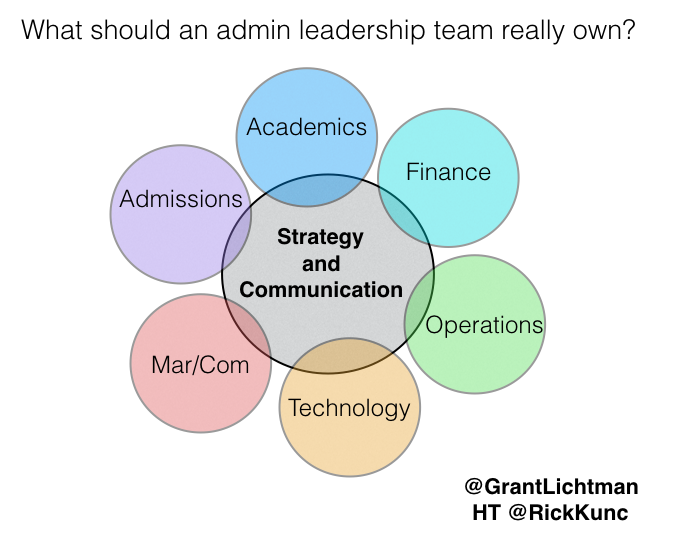

Faculty are hired because they are good teachers. For most schools this means that they either have a track record of being a good classroom teacher, or we think they will grow into that role. Few schools I know of ask for evidence on the CV of idea generation, imagining, development of innovation strategies, change management, or lead visioning. We tend to think of those strengths, to the extent we do actually think of them, as characteristic of top leadership. But let’s be honest: when the board hires a head of school, how many really consider “innovation superstar” ahead of “good fund raiser” and “good leader who will preserve that which we have built”? How many heads hire division leaders in order to take on the mantle of innovation superstar?

This is critical. Everything we know about innovation screams that it is about people and process. If we do not hire the people, the superstars of innovation to pull the process train, how will we succeed? Is outsourcing innovation to consulting firms a sustainable process? Some schools are solving this by hiring a Chief Innovation Officer or Chief Imagination Officer, or similar position. What a great step in the right direction! Innovative companies know that hiring this DNA is critical to success in a dynamic market, and they expand authority and responsibility to participate in innovation out to wide groups of employees. They hire smart, creative people and let them go a bit crazy. They assume that their employees can do the nuts and bolts of their job (teaching or leading, in our case), but the power they bring as a potential superstar of innovation is what will truly impact the institution over time.

Schools are not immune from the need to innovate; that much is getting to be pretty much accepted doctrine. Schools have not had to innovate in the past, so the basics are not in our DNA; understanding that gap is gaining traction. Now we need to devise solutions, and this latest research of how performance of humans is truly distributed must be part of crafting those solutions.

Grant, in fact, the primary reason for my career-path shift to education-innovation consulting is largely due to the fact that so few (if any) East coast schools are thinking about and acting on “Chief Innovation Officers” or “Directors of Innovation.” After making such a pitch to several Atlanta schools, I realized I would need to redirect my path a bit, at least for a few years until schools “catch up” with such thinking.