What does fighting a terror-based insurgency have in common with running a school? Fortunately the daily events are very different. But school leaders can learn critical lessons about managing large, complex organizations from how military, and increasingly business, leaders are learning to adapt to rapidly changing challenges.

What does fighting a terror-based insurgency have in common with running a school? Fortunately the daily events are very different. But school leaders can learn critical lessons about managing large, complex organizations from how military, and increasingly business, leaders are learning to adapt to rapidly changing challenges.

Retired General Stanley McCrystal led American forces in Iraq during some of the most violent phases of the post-Saddam years, when Al Qaeda and affiliated groups tore the country apart in an endless series of sectarian attacks that killed tens of thousands of innocent civilians. In Team of Teams, McCrystal openly reflects on how the powerful, resource-rich, highly structured, American forces were constantly surprised by the rag-tag, loosely-networked, improvisation of the insurgents. Over a period of two years, McCrystal and his staff had to completely re-think how large organizations are structured and managed, and then re-build everything they did in order to deal with a threat and an enemy that was vastly more nimble and dynamic. McCrystal realized that in a time when information flows faster than people can move, “Adaptability, not efficiency must become our central competency.”

This entire book is well worth the read, but here are a few key takeaways that I know will help inform the leadership training section of my own slide deck:

As we are finding in schools, teams that are most effective with dealing with rapidly changing challenges and opportunities:

- Swap the comfort of a rigid, industrial-type management architecture for organic fluidity.

- Are radically transparent in sharing of information that allows many more people to become informed leaders within their own spheres of work.

- Decentralize decision-making; titular leaders step back and allow others to lead.

- Dissolve the barriers (silos) that separate functional groups.

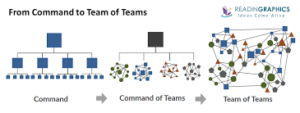

There were two key steps in converting the American Army into an effective counter-weight to the Iraqi insurgents: creating highly dynamic teams, and then combining those individual teams into a networked “team of teams”. Both of these steps resonate with business and school leaders who deal with less violent, but similarly volatile social and market demands.

Teams work well if they are founded on four principles: trust, a fusion of purpose, situational awareness, and the ability to think and act as a seamless unit. Teams that meet once a month around a table, organized by a dominant leader, focused on solving one problem in isolation, often comprised of members who are required to participate, fail in most or all of these four element. the first step for school leaders is to reflect: how can I apply these four elements of team design at my school?

Schools are complex organizations; one team focused on one topic or problem will not create an adaptable system. That requires the next step: creating a “team of teams” that integrate across traditional silos and boundaries. McCrystal suggests there are three main ways to create this team of teams:

- Create strong lateral connections: every individual does not have a relationship with every other individual. But everyone knows someone on every team

- Systemic understanding: Every team possesses a holistic understanding of the interaction between the moving parts.

- Decentralized control: Leaders provide information so that subordinates, armed with context, understanding, and connectivity, can take the initiative and make decisions

Team of Teams is on my “must read” list for edu-leaders and aspiring edu-leaders. Yes, this is a book about war, but much more than that, it is a book about how good leaders, when faced with challenges that seem to exceed their own capacity to deal with those challenges, adapt, change, and find a better way.

Leave A Comment