I have been following the Management Innovation eXchange site and recommend it to those who want to bring great ideas from the world of innovation thinking into our system of education. For a number of reasons, primarily related to both inertia and fear, education has been slow to adopt a world of proven innovation practices; translating these into our collective educator’s DNA is my primary focus.

Case in point is a great short article by Jim Stikeleather posted in February: “Innovation is a Process”. Jim points out that we can’t just hire creative, motivated people. We have to also put in place processes to get the most out of them. “Relying on random efforts risks an organization’s future successes.”

Leadership needs to create an expectation that innovation is NOT a stretch goal; it is a requirement. Jim offers three main principles to think about as we plan the effective adoption of innovation as a process:

Effective innovation requires rapid prototyping. The challenges of our current world, for any industry, are coming quickly. Public education has resisted this rate of change due to mind-warping cross-currents of expectation and self-interest of stakeholders. Private education has been resistant to change due primarily to our past success. But in the current environment we have to shorten the time cycle of try-fail-retry. As Jim says, save the myriad staff meetings, reports, and setting of standards until you are in production mode or you will surely kill the prototyping.

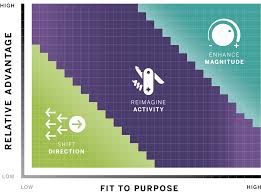

We also have to carefully target innovation. There are so many opportunities out there that we have to prioritize those that fit with our mission. We do this by first getting high above the weeds before we target in on an area of focus. Schools are generally not good at this; we tend to be inward focused on what we have done, instead of what we might do, and that can often lead to doubling down on past success. Leaders have to create an ongoing, sustainable system for leveraging their creative people into a place well above the weeds…and that is not common in schools.

Jim points out that great innovation starts with great ideas, and the best chances for true innovation come from unrecognized ideas; this is our most fertile ground for true competitive advantages. We uncover these by balancing between rigor and analysis on the one hand, and creative “ah-hahs” on the other. We will increase the frequency of encounters with well-balanced innovations if we increase the robustness of our personal and interscholastic networks of cooperation.

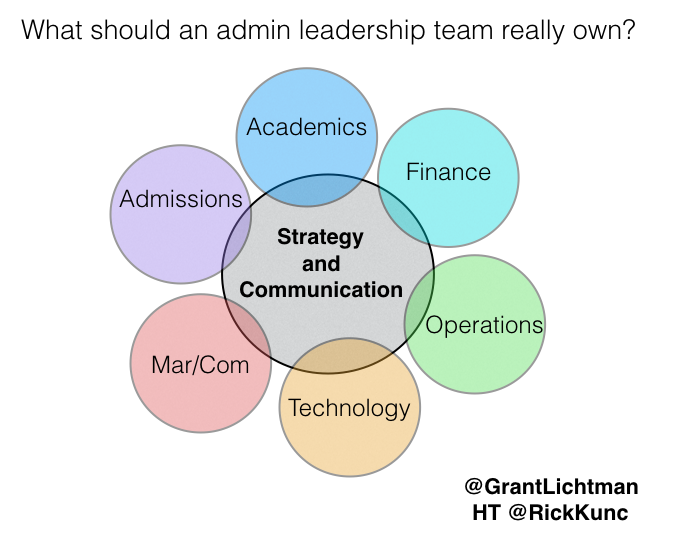

Leaders need to create time, space, and resources for their people to get together and launch into this process with faith in real outcomes and real change. This means breaking some of our existing institutional structures, no matter how comfortable we are within them. We are not going to outrun the pace of change unless we learn to really embrace new methods of running the race. The alternative is to watch the race go by.

I will be summarizing other articles from the MIX site in the days ahead.

Leave A Comment